The Cloisters Museum & Gardens: A Branch of The Metropolitan Museum of Art

99 Margaret Corbin Drive

Fort Tryon Park

New York, NY 10040

(212) 923-3700

Open: March-October 10:00am-5:15pm/November-February-10:00am-4:45pm

https://www.metmuseum.org/visit/plan-your-visit/met-cloisters

Fee: Adults $30.00/Seniors $17.00/Children $12.00/Members & Patrons and Children under 12 are free (prices do fluctuate).

Museum Hours:

Hours: Open 7 days a week

March-October 10:00am-5:15pm

November-February 10:00am- 4:45pm

Closed Thanksgiving Day, December 25th and January 1st.

*Some galleries may be closed for construction or maintenance.

TripAdvisor Review:

The Cloisters in December 2022

The entrance of the Cloisters for the “Holiday Decorating at The Cloisters” exhibition and talk

My blog on touring the Cloisters at the holidays:

I go to The Cloisters on a pretty regular basis, and they have interesting walking tours and lectures especially in the warm months. If you like Medieval or religious art, this is a museum that is worth visiting. It is out of the way and be prepared to walk up a hill but in the summer months, the view of the Hudson River is spectacular, and the gardens are beautiful.

The Cloisters in Fort Tyron Park

Don’t miss the walking tours and gallery talks at the museum. I have recently been to a series of walking gallery talks dealing with the history of Medieval arts. There were discussions on Medieval art between Christian and Muslim religions, Traveling the Silk Road and its influences on art in the regions and the collection and how it has improved and grown over the years. It seems there has been a uptick in this type of art.

This section of the shine is on a permanent loan from Spain

The building is just beautiful as it was created from pieces of religious sites all over Europe. Many of the doorways, cloisters (archways), stone work and fountains and windows come from churches that had been destroyed by wars over the past 600 years. Bits and pieces of all of the these buildings are displayed in the architecture of the museum itself. Some are on permanent loan to the museum from foreign countries.

Don’t miss the famous “Hunt of the Unicorn” tapestries that are on display here. They are quite a spectacular exhibit.

The ‘Hunt of the Unicorn’ tapestries

Be sure to visit the outside terraces of the Cloisters to see the views of the Hudson River below and the beautiful gardens of Fort Tyron Park where the building is located. It is a sea of green lawns and woods and beautifully landscaped flowering paths.

The Cloisters Gardens in the winter of 2022

The Cloisters Gardens in the Spring of 2024

The view from the gardens of the Hudson River

The view of the Hudson River in Spring 2024:

There is a nice café on property but there is also a small restaurant row on Dyckman Avenue at the foot of the park right near the subway stop. There are also many terrific Spanish restaurants on Dyckman Street as you walk down the block towards Fort George Hill.

‘Christmastide’ at The Cloisters:

I recently went to the Cloisters for a very interesting walking tour called “Holly & Hawthorne: Decorating for a Medieval Christmas” in 2019 and a similar tour in 2022 entitled “Holiday Decorations at The Cloisters” the use of plants like holly, mistletoe, pine and ivy were used in the winter months to decorate the churches and homes of the people until the Puritan influences took over.

Sampling of the plants used at the holidays in Medieval times.

(Part of the description of the tour in the guidebook-credit to the Met Cloisters):

“The wreaths and garlands that deck The Cloisters from early December until early January are made from plant stuffs associated with the Medieval celebration of Christmastide. This great feast embraced the twelve days between the Nativity and the Epiphany, which commemorated the visit of the Three Kings to the infant Jesus.

The Candelabras of the Cloisters.

Because pictorial representation of medieval Christmas decorations are rare, the Museum’s designs are based on evidence gleaned from carols, wassails, romances and artworks. Medieval churches and halls were decked for the season, a practice with roots in ancient custom. The early Church had banned the use of evergreens because of their ties with pagan winter festivals, such as the Roman Saturnalia. By the Middle Ages, these plants had been given Christian interpretations and were used to celebrate the feast days of the Church calendar. Bay Laurel, associated in ancient times with victory, became a symbol of the triumph of Christ and of eternal life.

By the Middle Ages, holly and ivy had been thoroughly Christianized, although mistletoe remained suspect. Ivy was identified with the Virgin and the red berries of the holly with the blood of Christ. The holly and ivy carols still sung today spell out these meanings older associations derived from pre-Christian winter festivals.

Apples and nuts, stored for winter consumption, were a conspicuous part of the Christmas feast, as they are today. It was also the custom in winter to wassail fruit and nut trees, to encourage them to bear plentiful crops in the coming year. Fruits and nuts were ancient symbols of fertility Christian meanings; in a medieval poem on the Nativity.

The Cloisters decorated for Medieval Christmas

The tour guide discussed by touring the paintings and tapestries where these symbolic plants took shape during this time. She even explained how ivy when it reaches sunlight that its shape goes from a three leaf shape to a heart shape which was symbolic during the Middle Ages. The gardens were a good source of inspiration for the holidays.

The stonework was decorated with garland and holly and flowering plants

The Cloisters decorated for Christmas

Don’t miss walking the halls and cloisters to look at all the decorations for the holidays. The museum keeps them simple and elegant but it really does put you in the holiday spirit. The use of flowering plants during the holiday season was not just related to the holiday season but they gave a nice smell to this musty churches and added a bit of cheer to the environment as well.

The flowers and pine when you enter The Cloisters

The “Holiday Decorations at The Cloisters” walking tour: December 2022:

The altar at The Cloisters

The Medieval plants for decorating the church including Bay Laurel, Myrtle, Rosemary and Cyclamen.

The flowers decorating the windows. Roses and pine.

Decorated altar candles

Decorated Altar Candles

Decorated Altar Candles

The Fruits and Ivy that decorate the archways at The Cloisters is changed regularly. Each of the ivy vines was encased in small water tubes that had to be changed each week.

The Christmas wreaths were decorated with fruits, ivy and pinecones

Along the walls and floors of The Cloisters were potted plants that would have been used to decorate churches during this time period. The flowering plants gave The Cloister such a nice smell and would have lighted up the inside rooms from the gloom of winter.

The hallways were lined with winter greens

The winter greens that lined the hallways of The Cloisters

The decorative winter greens lining the walls of The Cloisters

The orange tree was a symbol of gold and prosperity.

The Medieval door decorated for the holidays.

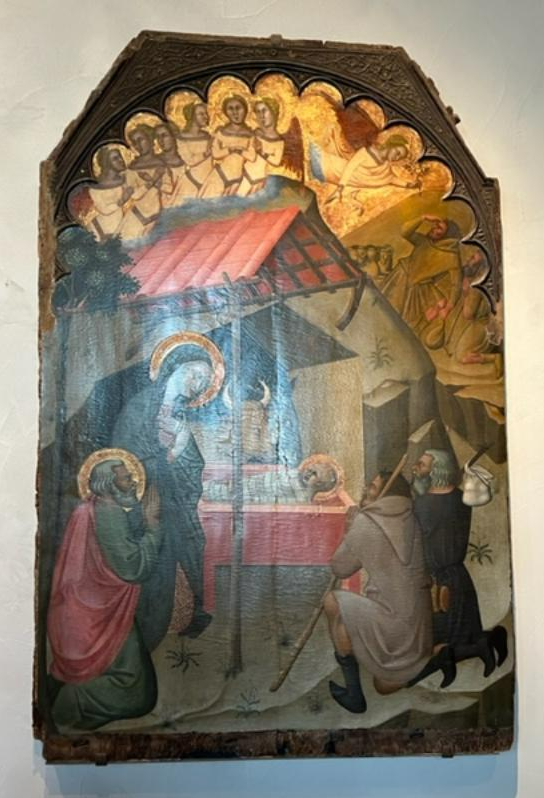

The tour guide also pointed out for the story of Christmas depictions of the three wise men in art all over the building and its importance in the holiday season. The story continued to develop on the three ‘kings’ who visited the holy child.

She explained that over the years it went from three ‘visitors’ wisemen’ that was loosely translated in older text to the modern development of ‘three kings’ from the continents of Asia, Africa and Europe. In 2024, I took a holiday tour on “Three Kings Day”, the celebrated the three kings and their visitation of the holy child.

The three Wise Men and the Virgin Mary

The three Wise Men and the Virgin Mary and Child as depicted in the painting

The three Wise Men in a more modern depiction. It seemed that the story morphed over time from three Kings, one being older, one younger and one with a darker complexion became a King from each continent to represent the diversity in the church and the spread of Catholicism.

The “Adoration of the Shepherds”

The Virgin Mary with the Christ child and the three wise men in the “Adoration of the Shepard’s”.

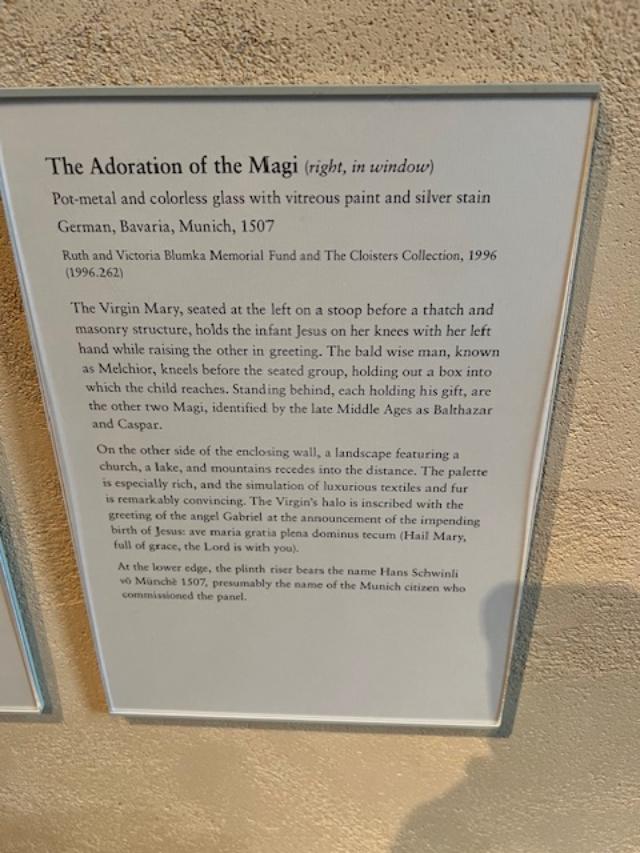

The “Adoration of the Magi”

The stained glass window of the “Adoration of the Magi”.

The “Thirty-Five Panels” of the Three Wiseman”

The Three Wisemen from the “Thirty-Two Panels”

The stained glass window of the “Three Scenes of the Infancy of Christ”

The “Three Scenes of the Infancy of Christ”

The “Christ is born as Man’s Redeemer” Tapestry.

The small section of the tapestry with the Three Wisemen.

Walking through the Cloisters during the holiday season.

The tour guide went onto explain that in more elaborate feasts, the utensils and items used during ceremonies would have been of the most elaborate that the church could show.

Elaborate vessels. plates, challices and specters used in ceremonies

Elaborate drinking glasses

I toured the Cloisters again in 2023 and saw the same symbols of Christmastime in the halls with elaborate floral displays and beautiful potted floral arrangements all over the building.

The hallways of the Cloisters decked with flowering plants.

The “Winter Roses” with other flowering plants.

More flowering plants lining the walkways.

Flowering displays

The winter plants of the Cloisters.

The Candelabra’s were quite elaborate.

I thought this Dragon painting was very interesting.

The Dragon Sign.

The Dragon Painting.

Spain 1000-1200: Art at the Frontiers of Faith” tour in 2021:

I visited again this Christmas holiday season in 2021 to see “Spain 1000-1200: Art at the Frontiers of Faith”, where the Catholic and Muslim Kingdoms of Spain influenced each other in the manner of decoration and art borrowing from each other. It was interesting to see how the two communities used each other’s art over time to develop an interesting hybrid of design that was both colorful and intricate.

“Spain 1000-1200: Art at the Frontiers of Faith” artworks

Another tour of the Cloisters that I attended was on the ‘Four Medieval Flowers: The Lily, Iris, Violet and Rose’. It was interesting how society of this era used the former Pagan and Roman/Greek symbols in their Christian religious art.

You see the Rose in the stained glass to represent strength and honor

You will see the meanings in the tapestries, stained glass art and in the sculpture to represent purity, rebirth and sexual symbols of the time. It seemed that the artisans of the time used ancient meanings to convey something that they could not out and out talk about.

In the “Hunt of the Unicorn” Tapestries you can see flowers such as Lilly, Violet and Iris woven into the work which may have meant it was a wedding present to the new owner. The tour guide said there was meaning in lots of the works which may have had a different purpose originally. It was a tour steeped in symbolism.

The Spring and Summer Time visits to The Cloisters and the Gardens:

The Cloisters in the Spring and Summer months is very different. The Gardens are in full bloom, the views of the Hudson River are still amazing and the flowers look and smell so beautiful. There are three sets of gardens in the Cloisters, the potted plants on the deck facing the Hudson River and the two Cloisters on the first level and the one in the Trie Cloister where the cafe is located. Each has their unique plantings.

The potted plants on the deck of The Cloisters in the Spring of 2024

As pretty as some of these plants are some are poisonous so you have to watch out.

The view from the back decks of the museum of the Hudson River

The view of the Hudson River

The gardens in The Cloisters

On Sunday, August 10th, I took an extensive garden tour of the separate Cloisters in each parts of the museum. The tour talked about the use of the Cloisters gardens of the past and they were used for herbs, remedies and for the simple pleasure of beauty, color and relaxation.

The religious symbols in the gardens

The gardens have been planted with historical accuracy but as the tour guide explained, to keep the gardens in bloom from the early Spring to the late Fall, you have to add different plants for color.

The beauty of the gardens in bloom

The beauty of the gardens in the Spring of 2024

The gardens were very popular over the weekend

Some of the Cloisters gardens produce fruits, vegetables and herbs that the staff can take home. These gardens show not just how beautiful they look but how people used them for every day purposes.

The gardens were popular that day

The beauty of the gardens

The gardens in the Spring of 2024

These walking tours at the Cloisters happen at 12:00pm and 2:00pm on the weekends when in season.

The beauty of the Cloisters

The herb gardens in the summer in 2025

The Cloisters Mission:

Welcome to The Cloisters, the branch of The Metropolitan Museum of Art devoted to the art and architecture of medieval Europe. Set on a hilltop with commanding views of the Hudson River. The Cloisters is designed in a style evocative of medieval architecture specifically for the display of masterpiece created during that era. Arranged roughly chronologically and featuring works primarily from Western Europe, the collection includes sculpture, stained glass, tapestries, painting, manuscript illumination and metalwork. The extensive gardens feature medieval plantings, enhancing the evocative environment.

The Gardens at the Cloisters in bloom

History of the Museum

John D. Rockefeller Jr. generously provided for the building, the setting in Fort Tryon Park and the acquisition of the notable George Grey Barnard Collection, the nucleus of The Cloisters collection. Barnard Collection, the nucleus of The Cloisters collection. Barnard, an American sculptor whose work can be seen in the American Wing of the Metropolitan, traveled extensively in France, where he purchased medieval sculpture and architectural elements often from descendants of citizens who had appropriated objects abandoned during the French Revolution. The architect Charles Collens incorporated these medieval elements into the fabric of The Cloisters, which opened to the public in 1938.

Romanesque Hall

Imposing stone portals from French churches of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries open onto a gallery that features rare Spanish frescoes and French sculpture.

Fuentiduena Chapel

The twelfth-century apse from the church of San Martin at Fuentiduena, Spain and the great contemporary fresco of Christ in Majesty from a church in the Pyrenees Mountains dominate the space. Sculpture from Italy and Spain enriches the chapel, which is the setting for a celebrated concert series.

Saint-Guilhem Cloister

The fine carving of this cloister from the monastery of Saint-Guilhem-le-Desert, near Montpellier, harmoniously and playfully adapts the forms of Roman sculpture in a medieval context. The plants depicted in the sculpture, acanthus and palm, are growing in pots near the small fountain. The gallery also features early sculpture from Italy, Islamic Spain and elsewhere in France.

Langon Chapel

Architectural elements from the twelfth-century church of Notre-Dame-du-Bourg at Langon near Bordeaux form the setting for the display of thirteenth-century French stained glass and important Burgundian sculpture in wood and stone.

Pontaut Chapter House

Monks from the Cistercian abbey at Pontaut in Aquitaine once gathered for daily meetings in this twelfth-century enclosure known as a chapter house. At the time of its purchase in the 1930’s by a Parisian dealer, the column supports were being used to tether farm animals.

The distinctive pink stone of this cloister, featuring capitals carved with wild and fanciful creatures, was quarried in the twelfth century near Canigou in the Pyrenees Mountains for the nearby Benedictine monastery of Saint-Michel-de-Cuxa. The typical cloister garden features crossed paths and a central fountain from the neighboring monastery of Saint-Genis-des-Fountaines. Both medieval and modern species of plants are grown in the garden. In winter, the arcades are enclosed and fragrant potted plants fill the walkways.

Early Gothic Hall

With thirteenth-century windows overlooking the Hudson River, the gallery features stained glass from France’s great churches, including Saint-Germain-des-Pres in Paris. Sculptures and paintings from France, Italy and Spain evoke the great age of cathedrals.

Nine Heroes Tapestries Room

From an original series of nine hangings created about 1400 for a member of the Valois court, the tapestries portray fabled heroes of ancient, Hebrew and Christian history, including the legendary King Arthur. It is among the earliest sets of surviving medieval tapestries.

Unicorn Tapestries Room

With brilliant colors, beautiful landscapes and precise depictions of flora and fauna, these renowned tapestries depicting the hunt and capture of the mythical unicorn are among the most studied and beloved objects at The Cloisters. Probably designed in Paris and woven in Brussels about 1500 for an unknown patron, these hangings blend the secular and sacred worlds of the Middle Ages.

Boppard Room

Stained glass from the fifteenth-century Camelite convent at Boppard-am-Rhein dominates one end of the room. Fifteenth-century panel paintings and sculpture from the Rhineland and northern Spain, a brass lectern, domestic furniture, Spanish lusterware, tapestries, metalwork and sculpture further evoke a sacred space.

Merode Room

One of the most celebrated early Netherlandish paintings in the world, the Merode Altarpiece, painted in Tournai about 1425-30, forms the centerpiece of this gallery. The altarpiece, intended for the private prayers of its owners, represents the Annunciation to the Virgin Mary taking place in a fifteenth-century household. Details of the scene are echoed in the late medieval furnishings of the room in which other works made for private devotion are also exhibited.

Late Gothic Hall

Large fifteenth-century limestone windows from the refectory of the former Dominican monastery in Sens, France, illuminate the hall, which showcases sculpture and altarpieces from Germany, Italy and Spain as well as a great tapestry from Burgos Cathedral.

Gothic Chapel

Beneath richly colored stained-glass windows from fourteenth-century Austria carved images from royal and noble tombs of France and Spain fill the chapel-like setting.

Glass Gallery

Silver-stained glass roundels decorate the windows of the Glass Gallery, complementing small works of art, many made for secular use, with their lively, sometimes worldly subjects. Carved woodwork from a house in Abbeville, in northern France, forms a backdrop for paintings and sculpture.

“Bonnefont” Cloister and Garden

Long thought to be part of the abbey at Bonnefont-en-Comminges, the elements of this cloister come instead from other monasteries in the region including a destroyed monastery in Tarbes. The herb garden contains more than 250 species cultivated in the Middle Ages. Its raised beds, wattle fences and central wellhead are characteristic of a medieval monastic garden.

Trie Cloister and Garden

The gardens at the Trie Cloister

The stone cloister elements were created primarily for the Carmelite convert at Trie-sur-Baise in the Pyrenees. The garden is planted with medieval species to evoke the millefleurs background of medieval tapestries, such as the Unicorn series.

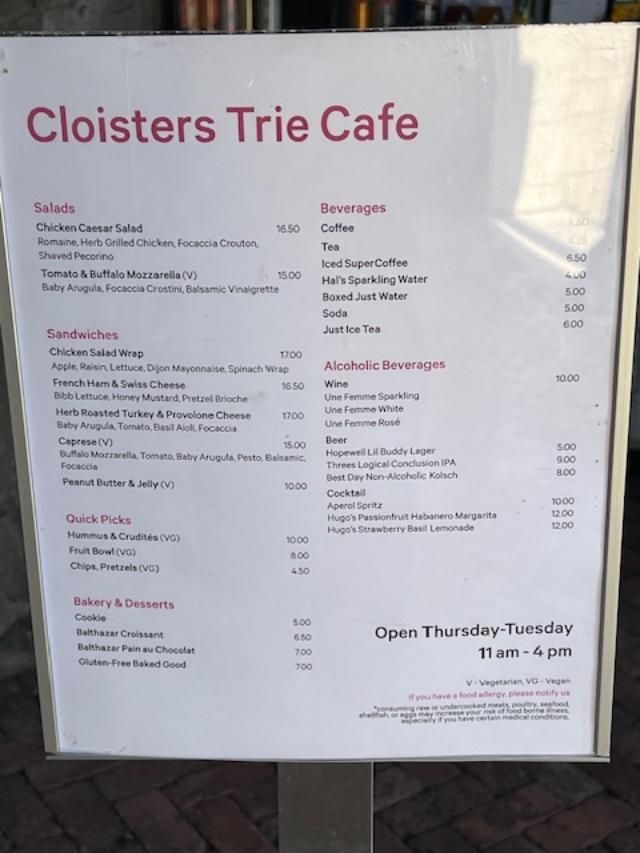

The Cloisters Trie Cafe is a seasonable restaurant that overlooks the Cloisters Gardens. This offers sandwiches , pastries and beverages and is a bit over-priced.

The Trie Cafe in the Cloister

The Trie Cafe is inside the Cloister

https://www.metmuseum.org/plan-your-visit/dining

Review on TripAdvisor:

*Please note that the prices in the restaurant do go up every year so please look to the website for updated prices.

The Treasury

An array of precious objects in gold, silver, ivory and silk reflects the wealth of medieval churches. Illuminated manuscripts testify to the piety and taste of royal patrons such as Jeanne d’Evreux, Queen of France; jewelry and a complete set of fifteenth-century playing cards suggest more worldly pastimes.

The Gift Shop:

Even the gift shop was decked in the holiday spirit

The gift shop has all sorts of themed items from the Medieval era.

The gift shop at The Cloisters

*Disclaimer: This information is taken right from the Cloisters pamphlet from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Please call the museum before visiting to see if anything has changed with the hours or days open. It is well worth the trip uptown to visit The Cloisters. Take the A subway up to 190th Street and take the elevator up to Fort Tryon Park and walk across the park.